My How and Why: Aliases, Functions, Symlinks and Shortcuts

[ ]I spend a decent amount of time at the commandline, for various reasons.

At work, it’s usually at Windows cmd; at home, it’s either cmd,

or bash on Debian. In both places, a major activity is working with Python,

virtual environments, git, etc.;

on the Linux box, I’m also doing a variety of other stuff as well.

On both platforms I have a bunch of shell invocations that I don’t

want to have to type out in full every time. This post lays out some ways

that I’ve found to implement these sorts of shortcuts, and which of these

approaches I currently prefer to use.

bash (Debian Linux)

Prior to writing this post, I had only been using symlinks and functions; now, I’m using some custom-defined aliases as well.

Aliases

bash aliases let you define static abbreviations

for shell commands (both builtins and executables). I’ve most often seen them used

to avoid needing to supply flags/arguments that are used on ~every invocation:

$ du -s

16720220 .

$ alias du="du -h"

$ du -s

16G .

$ alias pyc="python3 -c"

$ pyc 'print("Hello!")'

Hello!

I actually hadn’t used any of these before researching them for this post;

but, now that I’ve looked closely, I’ve added a few to

a new ~/.bash_aliases (they could also be added directly into

~/.bashrc or ~/.profile):

# ls, full listing & show dotfiles

alias lla="ls -la"

# ls, minimal display

alias l1="ls -1"

# Always human-readable du

alias du="du -h"

# Always human-readable df

alias df="df -h"

# Grepped history and ps

alias hg="history | grep "

alias psag="ps aux | grep "

# Quick access to apt update and upgrade

alias aptupd="sudo apt-get update"

alias aptupg="sudo apt-get upgrade"

Note that it does work fine to ‘redefine’ an existing command to include default

options/flags, as was done above for du and df—alias doesn’t

recurse its substitutions. In situations like this, the original command

can be accessed by enclosing it in quotes:

$ du -s

16G .

$ "du" -s

16695720 .

However, as I did for lla and l1,

in most cases I expect I’ll define aliases as new names,

so that I can get at the original commands without quoting them.

Note also that aliases cannot contain explicit positional arguments. Any arguments passed to the alias always get transferred directly to the tail of the expanded command.

Functions

bash functions

are a considerably more flexible means for defining

custom commands. They can enclose multi-line commands, and can use

arguments in arbitrary ways. The syntax is a bit unusual, as can be

seen in this function I wrote for activating a python virtual environment

in a sub-directory of the current working directory:

vact () {

source "env$1/bin/activate"

}

The parentheses will always be empty; they’re purely

a syntactic marker to tell bash that you’re defining a function.

Note that even though this function is only a single command,

it could not be implemented as an alias, since the argument

indicating which environment to activate

has to be substituted into the middle of the command.

(Most of the time, I use this function without an argument, which

will activate the environment in env; however, if I define

multiple environments in a common location, this lets me activate

a specific environment: $ vact foo would activate

an environment residing in envfoo.)

Note that, unlike with aliases, arguments passed to a function call are NOT automatically passed through to any particular command inside the function body—you have to specifically indicate where they should be used:

$ pygood () { python3 $*; }

$ pybad () { python3; }

$ pygood -c "print('Hi')"

Hi

$ pybad -c "print('Hi')"

Python 3.7.3 (default, Apr 3 2019, 05:39:12)

[GCC 8.3.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

As with aliases, functions can put directly into

~/.profile or ~/.bashrc,

or kept segregated in ~/.bash_aliases.

Executable Symlinks

Aliases and functions are great for abbreviating direct invocations

from the command line, but they have some disadvantages

as compared to symlinks

(created with ln -s [target] [new link]).

One significant disadvantage is the fact that aliases and functions

are defined per-user, whereas symlinks exist on the filesystem

and (given suitable permissions) can thus be used by anyone

logged in to the machine. Also, since symlinks provide an

effectively invisible pass-through to the target executable,

they can be used in complex invocations in ways that

aliases and functions might not support.

Initially, I thought that piped command sequences were one

example of this, but it turns out that both aliases and functions

handle pipes and input redirects just fine:

$ alias py="python3"

$ py3 () { python3 $*; }

$ echo "print('Hi')" | python3

Hi

$ echo "print('Hi')" | py

Hi

$ echo "print('Hi')" | py3

Hi

$ echo "print('Hi')" > in

$ py < in

Hi

$ py3 < in

Hi

Depending on your needs, it may make sense to put some symlinks in

a central location that won’t conflict with the system

package manager. It sounds like

/usr/local/bin

is a pretty standard location for things like this, and looks to be included

on PATH by default. If you would want any of these symlinks to

be available to users only if they want to opt-in to them,

something non-standard like /usr/custom/bin is what I would use.

(For more information on the various bin directories,

see here.)

For my use cases to date, though,

I’ve pretty much always created my symlinks

in a per-user fashion, placing them in a ~/bin directory,

since I haven’t needed to make them accessible to others.

I’ve done this even though I’m using multiple logins

(to keep various responsibilities separated), because most of the

commands are specific to each of the different logins I use

to keep concerns segregated. However, for my custom Python

builds, as described below, I’m considering moving their

installation locations to someplace centralized,

such as /usr/custom, and switching to building with

the superuser. This would in particular avoid the need to rebuild

Python for each user. I would still curate the symlinks per-user, though,

in ~/bin.

In order to make the symlinks available for execution,

I just add a command in ~/.bashrc to prepend ~/bin

(in its fully expanded form) to PATH:

export PATH="/home/username/bin:$PATH"

Other paths, such as /usr/local/bin, can be added to

PATH in the same fashion.

On all subsequent logins with username, these symlinks will be available

for direct execution in the shell.

As noted above, my main current use for these symlinks

is to allow easy access to multiple

locally-compiled versions of Python. While there are tools

out there that provide for automatic management of Python

versions

(e.g., pyenv ![]() and

and pyflow ![]() ),

I would rather have more direct control over

what’s installed and how it’s compiled. For per-user installs,

I install my custom

Pythons into

),

I would rather have more direct control over

what’s installed and how it’s compiled. For per-user installs,

I install my custom

Pythons into ~/python/x.y.z/, and then

create symlinks in ~/bin:

$ cd /home/username/bin

$ ln -s /home/username/python/3.8.0/bin/python3.8 python3.8

This setup works really well with

tox,

such that the Python executables can be set just as:

[testenv:linux]

platform=linux

basepython=

py39: python3.9

py38: python3.8

py37: python3.7

py36: python3.6

py35: python3.5

The packages associated with each Python version can be changed

with pip per usual:

$ python3.8 -m pip ...

And, new virtual environments can be created with a given Python version via one of:

$ python3.8 -m virtualenv env --prompt="(envname) "

or

$ python3.8 -m venv env --prompt="envname"

Obviously, the first option only works after a python3.x -m pip install virtualenv.

Windows

Prior to doing the research for this post, as far as I knew

Windows cmd wasn’t nearly as flexible an environment for defining

these sorts of helpers—the only option was to use batch files.

One alternative might have been to switch to PowerShell, but cmd

was working well enough for me and I had no real desire to take the time

to learn a completely new (and from what I could tell crushingly verbose) syntax.

So, my approach for this on Windows has always been to add a per-user bin directory

and put it on %PATH%, in a fashion directly analogous to the above approach

for bash. The Windows 10 equivalent of ~ is usually

C:\Users\Username, but whatever the location of the home directory

for a user actually is, it’s stored in the environment variables as

%USERPROFILE%. Once created, that directory needs to be added to %PATH%;

Windows defines both a system-wide and a user-specific PATH, and since

I’m usually creating a user-specific %USERPROFILE%\bin, I usually

add it to the user-specific %PATH%. There’s a good discussion

of %PATH% and how to add entries

here on SuperUser.

With the bin directory created and on %PATH%,

I just create batch files for everything I want to streamline in there.

For functionality that’s like a bash alias or symlink, the batch files

typically are simple two-liners. For commands that lead to further

interaction at the command line, I’ll use:

%USERPROFILE%\bin\python3.8.bat

===============================

@echo off

C:\Python\python38\python.exe %*

For commands that kick off a GUI application (e.g., WordPad), or an application that I always want to run in the background as a new process, I’ll use:

%USERPROFILE%\bin\wordpad.bat

=============================

@echo off

start "C:\Program Files\Windows NT\Accessories\wordpad.exe" %*

In these, @echo off is the first line used in basically every

DOS/Windows batch script ever

(why is echo on by default?!),

to turn off echoing to stdout of the commands executed by the script.

The %* argument

passes the entire set of arguments provided to the script (if any)

through to the command to be run.

Another thing that I learned in the course of researching this post is that

cmd batch files do handle content either piped in from a preceding command

or redirected from a file on disk. Per here,

this content stream is implicitly provided to the first command of the batch

file that is capable of processing it. Thus, both of these invocation cases work

fine with the above python3.8.bat:

C:\Temp>type test.py

import sys

from pathlib import Path

print(sys.version_info)

print(str(Path().resolve()))

C:\Temp>type test.py | python3.8

sys.version_info(major=3, minor=8, micro=1, releaselevel='final', serial=0)

C:\Temp

C:\Temp>python3.8 < test.py

sys.version_info(major=3, minor=8, micro=1, releaselevel='final', serial=0)

C:\Temp

For actions that are more complex, analogous to the use-case of bash functions,

the script typically ends up structured differently, and sometimes ends up being longer.

For example, this is my Windows equivalent of that vact helper for

activating virtual environments:

%USERPROFILE%\bin\vact.bat

==========================

@echo off

env%1\scripts\activate

So, while I can’t do everything with batch files in cmd that I can

in bash, I can get pretty darn close—certainly enough to handle

all of my routine tasks, and even most non-routine ones.

In the course of researching for this post,

I discovered that apparently Windows does support functionality for

symlinks

(since Windows Vista!), and provides the

DOSKEY macro mechanism that

behaves somewhat similar to bash aliases.

They both have significant downsides/problems, though, that make me

strongly prefer the batch-file approach.

Symlinks don’t seem to work correctly out of the box in all situations

for executing Python, one of my must-have use cases—it appears that they sometimes

don’t set various elements of the execution context correctly, at minimum the path.

They are created with the mklink command, which has to be run in

a console with administrator privileges (a further annoyance;

press Win+R to open the “Run” dialog, type cmd,

then press Ctrl+Shift+Enter for elevated execution):

C:\Users\Username\bin>mklink python3.8-sl C:\Python\Python38\python.exe

symbolic link created for python3.8-sl <<===>> C:\Python\Python38\python.exe

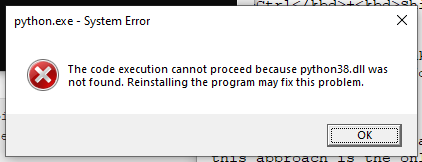

However, execution of Python via this symlink doesn’t work reliably. It functions okay on my work PC, but when I try something like this at home…

C:\Users\Username\bin>cd \temp

C:\Temp>python3.8-sl test.py

… I get a system error:

So, not knowing exactly what’s going on here, and given the friction involved in creating the things, I’ll be continuing to avoid Windows symlinks for the time being.

DOSKEY aliases work for a subset of applications, but have a number

of key limitations. They’re created and used using a syntax similar to bash’s:

C:\Temp>doskey python38=C:\Python\Python38\python.exe $*

C:\Temp>python38

Python 3.8.0 (tags/v3.8.0:fa919fd, Oct 14 2019, 19:37:50) [MSC v.1916 64 bit (AMD64)] on win32

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> ^Z

C:\Temp>python38 -c "print('HELLO WORLD')"

HELLO WORLD

The $* argument serves the same role as in bash functions, passing through

to the expanded command all arguments provided to the alias/macro.

Unfortunately, unlike with batch scripts, you can’t pipe text into a DOSKEY macro:

C:\Temp>type test.py | python38

'python38' is not recognized as an internal or external command,

operable program or batch file.

Also, per here, DOSKEY macros can’t

be used within batch files, and setting them up to be loaded at the start

of every console session requires a registry modification. So, batch files again

remain my preferred Windows solution.